A Titanic Timeline Part II

/Last time, we began with a glimpse into Titanic’s maiden voyage, beginning with the preparations in Southampton on April 5, 1912. On Sailing Day, April 10th, Titanic departed Southampton on what would be her only voyage, carrying 2,208 passengers and crew.

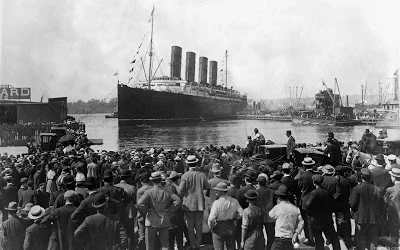

leaving southampton

Titanic departing Southampton April 10, 1912

The Titanic headed across the English Channel for Cherbourg, France, where 24 passengers disembarked and 274 passengers came aboard via tenders. Just after 8:00 pm, the ship was again under way. The first dinner on board had been served in all classes, and passengers spent the evening acquainting themselves with the ship, preparing their children for bed, or strolling the pristine outside decks to gaze at the brilliant canopy of stars.

April 11. At 11:30 am, Titanic dropped anchor two miles offshore at Queenstown, Ireland. Tenders transported 120 passengers and 1,385 sacks of mail to the ship. Two hours later, the Titanic headed out to sea. For most of those on board, they would not see land again.

last_titanic_photo leaving Queenstown

Last photo of the ship as it left Queenstown

April 12. Passengers spent the next three days enjoying the ship’s many amenities. Even third class passengers marveled at the bright and spacious public rooms and delicious food. There were few scheduled activities, other than dining hours.

April 13. First class passengers looked forward to the noon posting each day in the smoking room of the previous day’s run. From Thursday, April 11 to Friday, April 12, the ship traveled 386 nautical miles. From Friday April 12 to Saturday April 13, 519 miles, and from Saturday April 13 to Sunday April 14, 546 miles were logged.

titanicsmoking room

April 14. On Sunday, a church service was held in the first class dining saloon. The temperature dropped, and Titanic received several ice warnings over the wireless from other ships in the area. Around 6:00 pm, Captain Smith gave orders for her course to be altered slightly due to the warnings. At 10:00 pm, lookouts Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee took their post in the crow’s nest. At 11:30 pm, Fleet sighted an iceberg and warned the officers on the bridge. Quartermaster Robert Hichens responded immediately to the order to turn the ship ‘Hard-a-starboard.’ The ship turned, but not enough. Less than a minute passed from the moment Fleet sighted the iceberg to collision.

crows nest

Crow's nest half-way up mast on left. The bridge, with several windows, is behind it on top deck

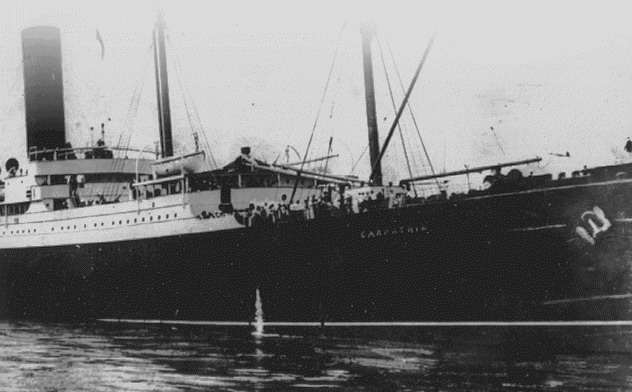

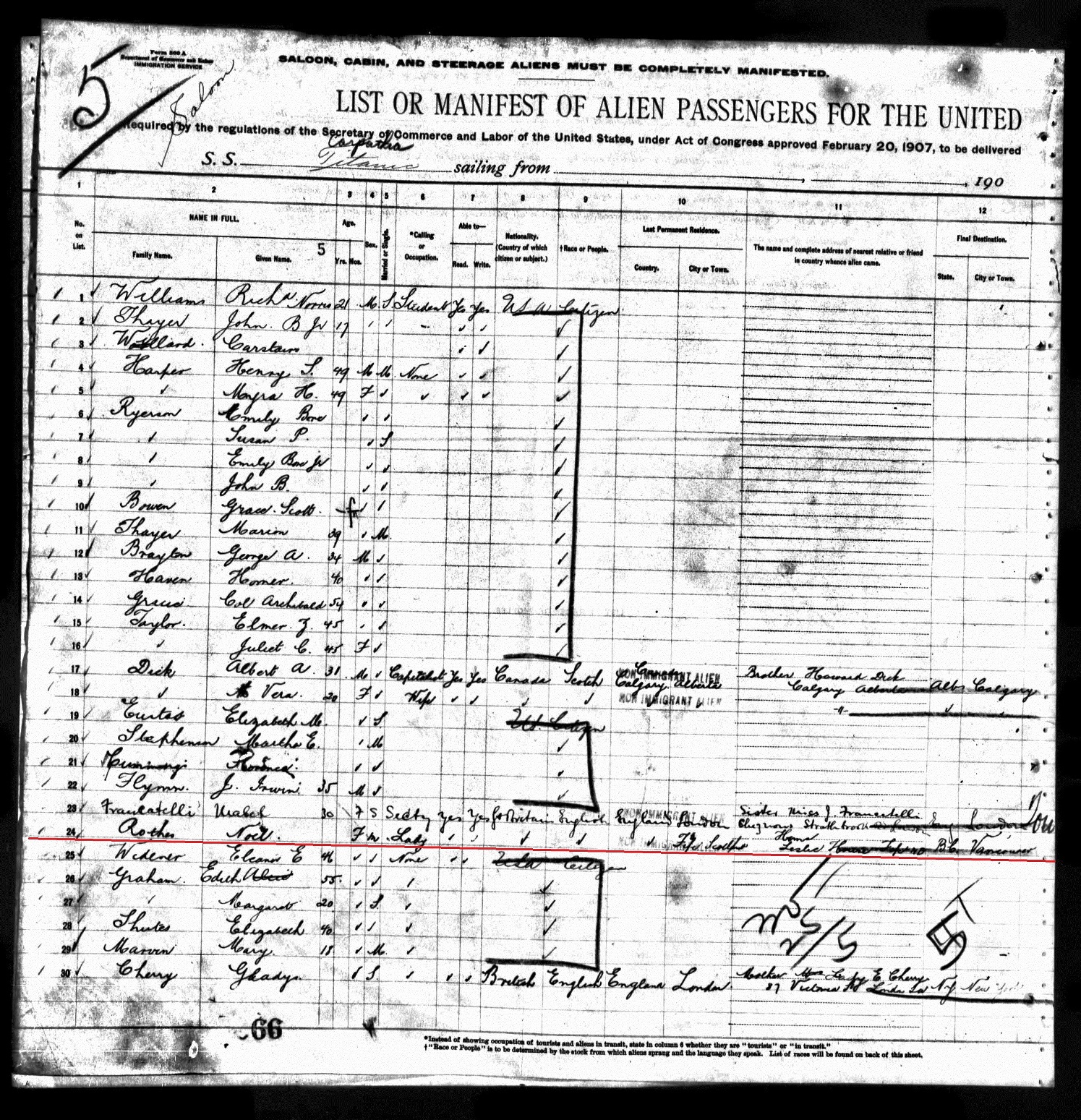

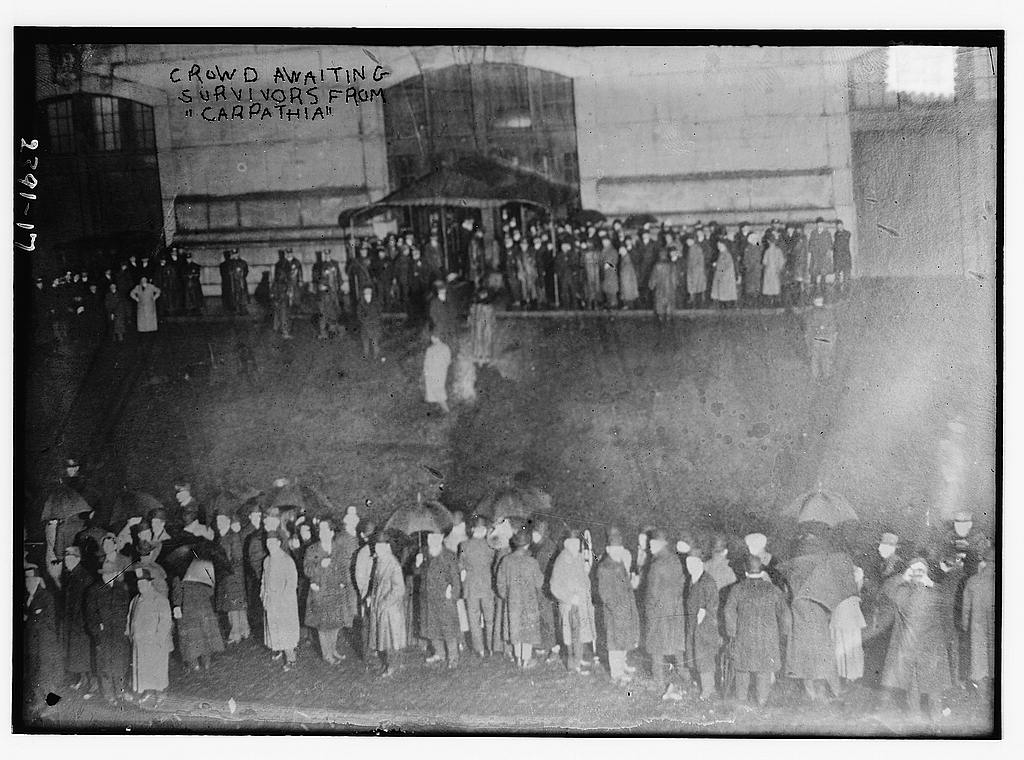

April 15. With approximately 1500 passengers and crew still on board, the RMS Titanic sank in the north Atlantic at 2:20 am. Hundreds fell to their deaths, drowned, or died of hypothermia in the frigid waters. All twenty lifeboats, many carrying fewer than their capacity, drifted in a calm, frigid sea until dawn. The RMS Carpathia, having received Titanic’s distress calls, raced through the ice field to rescue the surviving 712 men, women, and children. Carpathia passengers and crew did their best to accommodate and comfort those from the Titanic. Captain Arthur Rostron set a course for New York.

lifeboats_at_carpathia

Titanic lifeboat alongside Carpathia

Photo credits: Encyclopedia-titanica.org, irishecho.com, maritimequest.com