The Boat That Went Back (Part I)

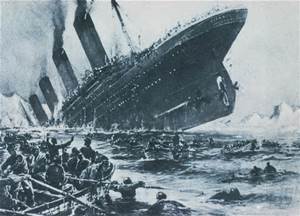

/After the Titanic struck an iceberg on the night of April 14, 1912, it soon became apparent that the ship would sink within a few short hours. All sixteen lifeboats plus four collapsible boats were lowered to the Atlantic’s surface, some only half-filled with passengers and crew.

Of the 2,223 souls onboard, only 706 survived by escaping the ship on a lifeboat. After the sinking at 2:20 am, hundreds cried for help in the water. Those in the lifeboats claimed it sounded like one long wailing chant, and was the worst sound they ever heard.

photo credit - Titanic Universe

Many of those in the water wore their lifebelts, but with the water temperature at 28 degrees Fahrenheit, hypothermia soon set in. After about twenty minutes, their cries began to diminish. By 3:00 am, all was quiet.

Passengers in many of the lifeboats wanted to go back and try to rescue any they could. They begged those in charge of their boats to go back, but were told they were too far away, or those in the water would swamp the boat. In Lifeboat 8, the Countess of Rothes and a few others wanted to return, but the other passengers overruled them. In Lifeboat 5, Ruth Dodge wanted to go back, but the others disagreed. She was so disgusted with them that she later switched boats. In Boat 6, Quartermaster Robert Hitchens told his passengers, “It’s our lives now, not theirs.”

The Countess of Rothes (photo credit - Titanic Forum)

Lifeboat 4 had been the last boat to leave Titanic’s port side, with two sailors and 42 passengers aboard. Among them were Mrs. John Jacob Astor and several more ladies from first class. As it launched, the women’s husbands stood on the deck together, quietly watching. Thirty-nine-year-old Quartermaster Walter Perkis, still on deck, was then sent to the boat to take command. He had to slide down a 70-foot rope to reach it.

As the Titanic sank, Boat 4 passenger Mrs. Emily Ryerson, wife of steel magnate Arthur Ryerson of Philadelphia, heard someone say, “Pull for your lives or you’ll be sucked under.” She saw Mrs. Astor helping with the rowing, but there didn’t seem to be any suction. The lifeboat hadn’t gone far when the occupants began hearing the agonizing cries from those in the water.

Mrs. Emily Ryerson (photo credit - aftitanic.com)

Perkis told the US Inquiry, “…we picked up eight men that were swimming with life preservers. Two died afterwards in the boat. One was a fireman and one was a steward.”

Mrs. Ryerson stated, “…we dragged in six or seven men. They were so chilled or frozen already they could hardly move. Two of them died in the stern later, and many were raving and moaning and delirious most of the time.”

In Lifeboat 14, Fifth Officer Harold Lowe, 29, blew his whistle and ordered that several boats near him, including Boat 4, tie together and redistribute the passengers more evenly. When that was done and the cries from the water subsided a bit, Lowe felt it was safe to return to rescue people from the water. Until then, he felt the boats would be sunk by hundreds of people attempting to climb in.

(To be continued next week)