The First to See the Iceberg

/Three watch groups of two men each took turns in Titanic’s crow’s nest during her maiden voyage. At 10:00 pm on the night of April 14, 1912, Frederick Fleet, 24 and Reginald Lee, 42, climbed 75 feet to their station. They’d each served several years aboard other ships in various capacities and were considered experienced lookouts. The air temperature hovered near 30 degrees, but with Titanic running at 22.5 knots, Fleet and Lee were bound to feel much colder in their perch high above the ship.

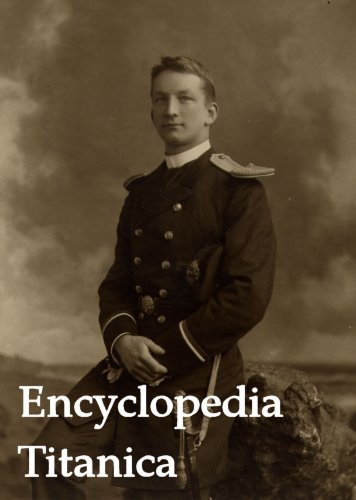

Frederick Fleet

Reginald Lee

A half hour before they came on duty, a message had been sent to the crow’s nest to watch for ice. But the warning was not passed on to Fleet and Lee. Perhaps if they’d been aware of the possibility of ice, they would have paid closer attention. Another mistake that caused much discussion after the disaster was that the binoculars normally available for the lookouts to use were missing. They may have aided the men as they scanned the horizon, although from the crow’s nest it was possible to see a distance of 11 miles, especially on such a calm, clear night.

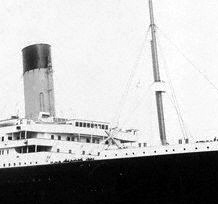

Titanic's bridge (center) and crow's nest on mast (right)

For the first 1 ½ hours into their watch, the men saw nothing. Then around 11:30, Fleet noticed a slight haze along the horizon. It almost didn’t seem worth mentioning to Lee. But a few minutes later a black object suddenly appeared in their path. It could only be an iceberg. Fleet rang the bell three times, indicating something directly ahead. He picked up the telephone which rang in the wheelhouse.

Sixth Officer Moody answered. “What do you see?”

Fleet replied, “Iceberg right ahead!”

From the bridge outside the wheelhouse, First Officer William Murdoch saw the iceberg by then himself. He gave the order, “Hard a’ starboard,” which would cause the ship to turn to port. Fleet waited in the crow’s nest, watching the bow gradually swing to port. At first, it seemed Titanic would clear the 60-foot berg, but as it moved alongside the starboard bow, Fleet and Lee heard it scrape the hull as ice fell on the decks. The time between the sighting of the iceberg and the collision had been less than a minute.

Frederick Fleet

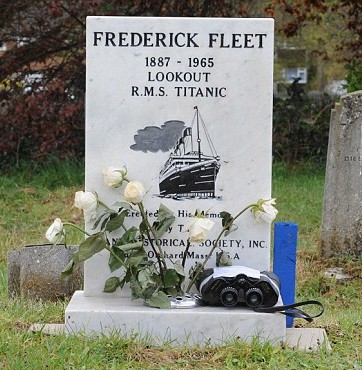

Both Fleet and Lee survived the sinking and later testified at the inquiries into the disaster. Reginald Lee died a year later of pneumonia while working aboard the Kenilworth Castle. Frederick Fleet returned to sea for the next 24 years, then worked for Harland and Wolff as a shipbuilder. His wife died in 1964, and his brother-in-law, with whom the couple lived, evicted him. He committed suicide two weeks later and was buried in a pauper’s grave. In 1993, donations for a proper headstone were made to the Titanic Historical Society.

Headstone for Frederick Fleet. Binoculars were left by a visitor.

Photo credits: Encyclopedia Titanica and titanicuniverse.com