Just Missed the Titanic - Part III

/We’ve been taking a break this summer from the stories of those who were on board the Titanic to see who literally missed the boat.

At the age of 20, Guglielmo Marconi became intrigued with the discovery of “invisible waves” from electromagnetic interactions. The son of a wealthy Italian landowner, Marconi began building his own equipment and was soon transmitting signals miles away. In 1896, he and his mother traveled to London where he found others willing to invest in his work. Before long, he applied for his first patents and set up a wireless station on the Isle of Wight. By 1899, signals from Marconi’s station had crossed the English Channel.

marconi

Guglielmo Marconi

He wanted to improve his wireless system in order to broadcast across the Atlantic. Experts argued that radio waves would only travel in straight lines and the curvature of the earth would not allow transmitting at so great a distance. But Marconi persevered. He set up a wireless station in Cape Cod, Massachusetts, with the hope of receiving a signal sent from England. When that failed, he tried a shorter distance—Cornwall to Newfoundland. In 1901, after several attempts, a faint signal was picked up—3 dots, the letter “s” in Morse Code.

In 1909, Marconi received the Nobel Prize in Physics, which he shared with physicist Karl Braun, the inventor of the cathode-ray tube. In his acceptance speech, Marconi claimed he was “more a tinkerer than a scientist” and wasn’t sure how his invention worked.

Marconi continued to make improvements to his wireless radio system. Shipping companies soon recognized its usefulness for communication and navigation. “Marconi Men,” trained in the operation of the equipment, became a vital part of every large ocean-going vessel. On Titanic, Harold Bride and Jack Phillips, with previous experience at Marconi stations and on ships, prepared for her maiden voyage.

titanic_marconi_room

Replica of Titanic's Marconi Room

White Star Line officials invited Marconi to sail on Titanic to New York. He declined, and took the Lusitania three days before Titanic left Southampton. Years later, his daughter claimed he’d had paperwork to do and preferred the stenographer aboard that ship.

During the sinking of the Titanic, Bride and Phillips worked valiantly to send emergency messages to ships in the area. Several responded, but it was the RMS Carpathia who eventually arrived at the scene and saved over 700 lives. Without the Marconi system in place, many more lives, if not all, would certainly have been lost. Although there were reports of Carpathia wireless operators being instructed to withhold information from the press until the ship arrived in New York, Marconi was soon hailed as one of the heroes of the disaster because of his invention.

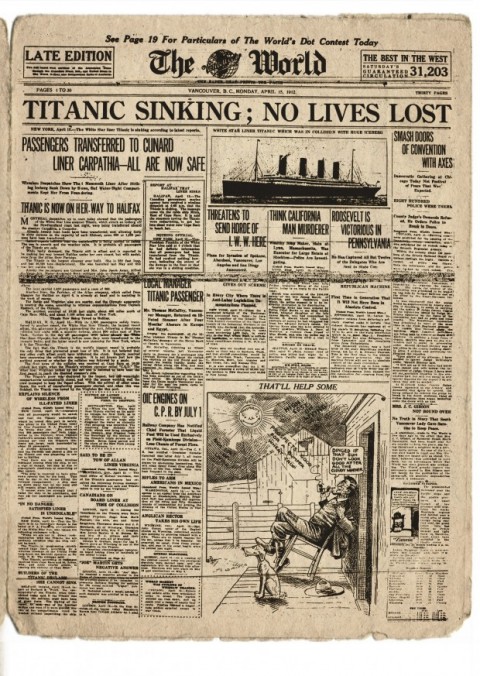

Marconi message sent from Olympic

Marconi message sent from RMS Olympic to Titanic

In April 1915, Marconi was aboard the Lusitania once again. A month later, she was sunk by a German U-boat. He continued to make improvements to his inventions, and died in 1937 in Rome. Radio stations in America, England, and Italy observed several minutes of silence in his honor.

Photo credits: History.com, Library of Congress, Titanicpigeonforge.com