One Survivor's Happy Ending

/In May 2016, I wrote the following post about third class passenger Sarah Roth. Quite recently I heard from two of her grand-nieces who have asked that I share some additional information about Sarah's family and the surviving members. I love to hear from readers, and especially anyone with a direct connection to those who experienced Titanic's one and only voyage. I believe it's important to keep their memory alive, including any up-to-date information. Today, I'm re-posting the original article, with the addition of what I have now learned about Sarah's family.

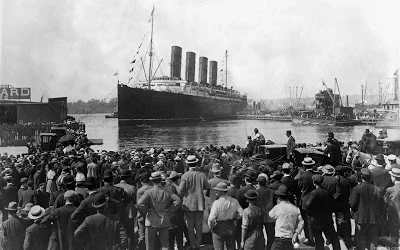

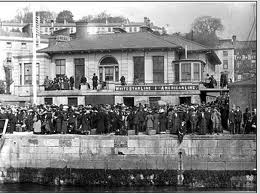

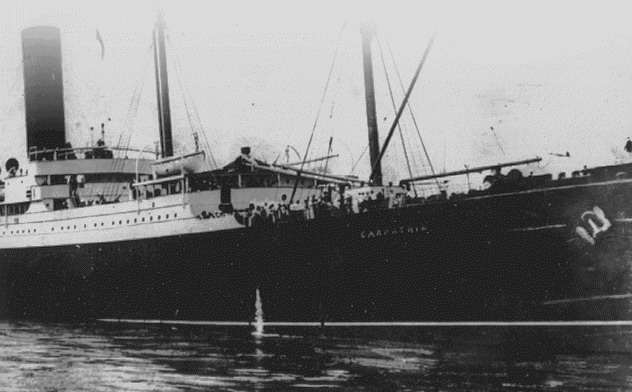

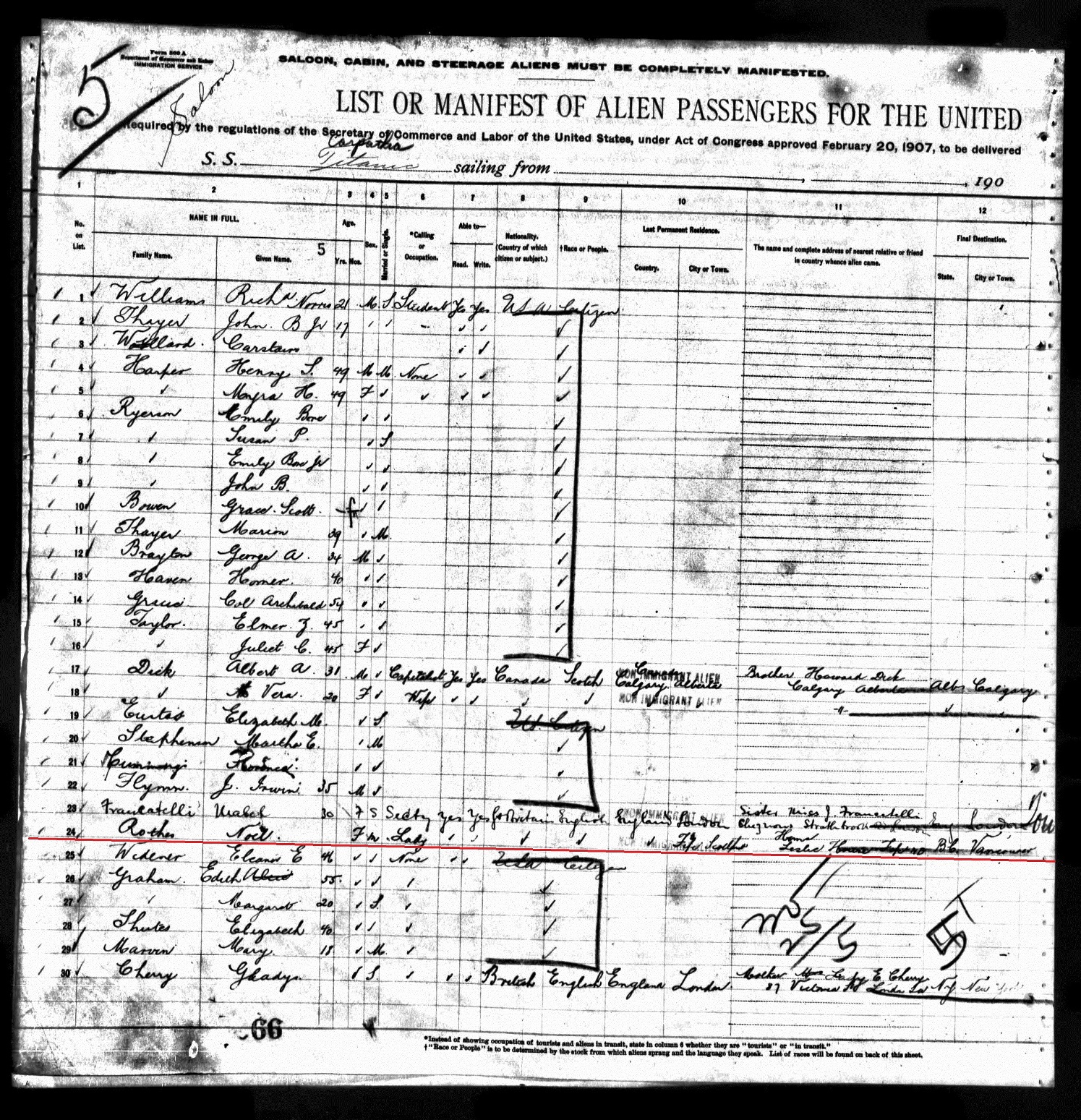

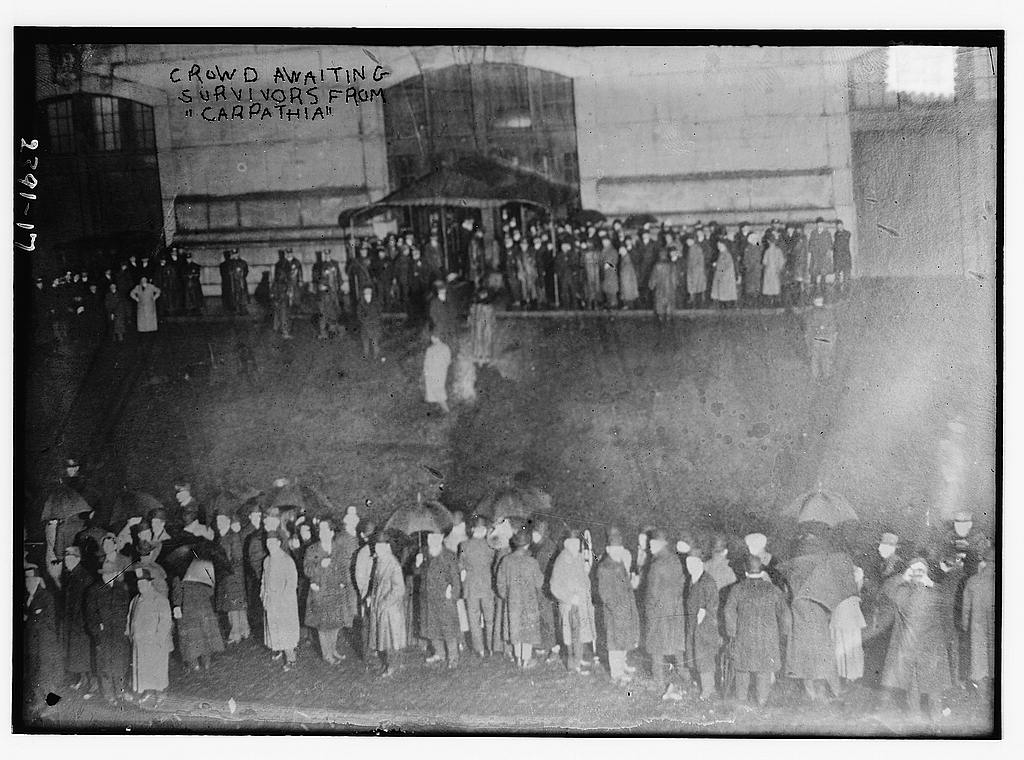

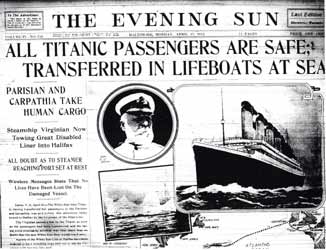

On April 18, 1912, the survivors of the Titanic left the Carpathia after it docked in New York City. Many of the sick and injured were taken by ambulance to nearby St. Vincent’s Hospital. Among them was 26-year-old Sarah Roth, an immigrant from England who had boarded Titanic as a third class passenger.

Sarah had been engaged for several years to Daniel Iles, a grocery warehouseman. Daniel emigrated to New York in 1911 and became a department store clerk, saving money until he had enough to send for Sarah. At home, Sarah waited and sewed her wedding dress. Finally, Daniel purchased Sarah’s third class ticket to New York on Titanic. They would meet in New York, where they would be married.

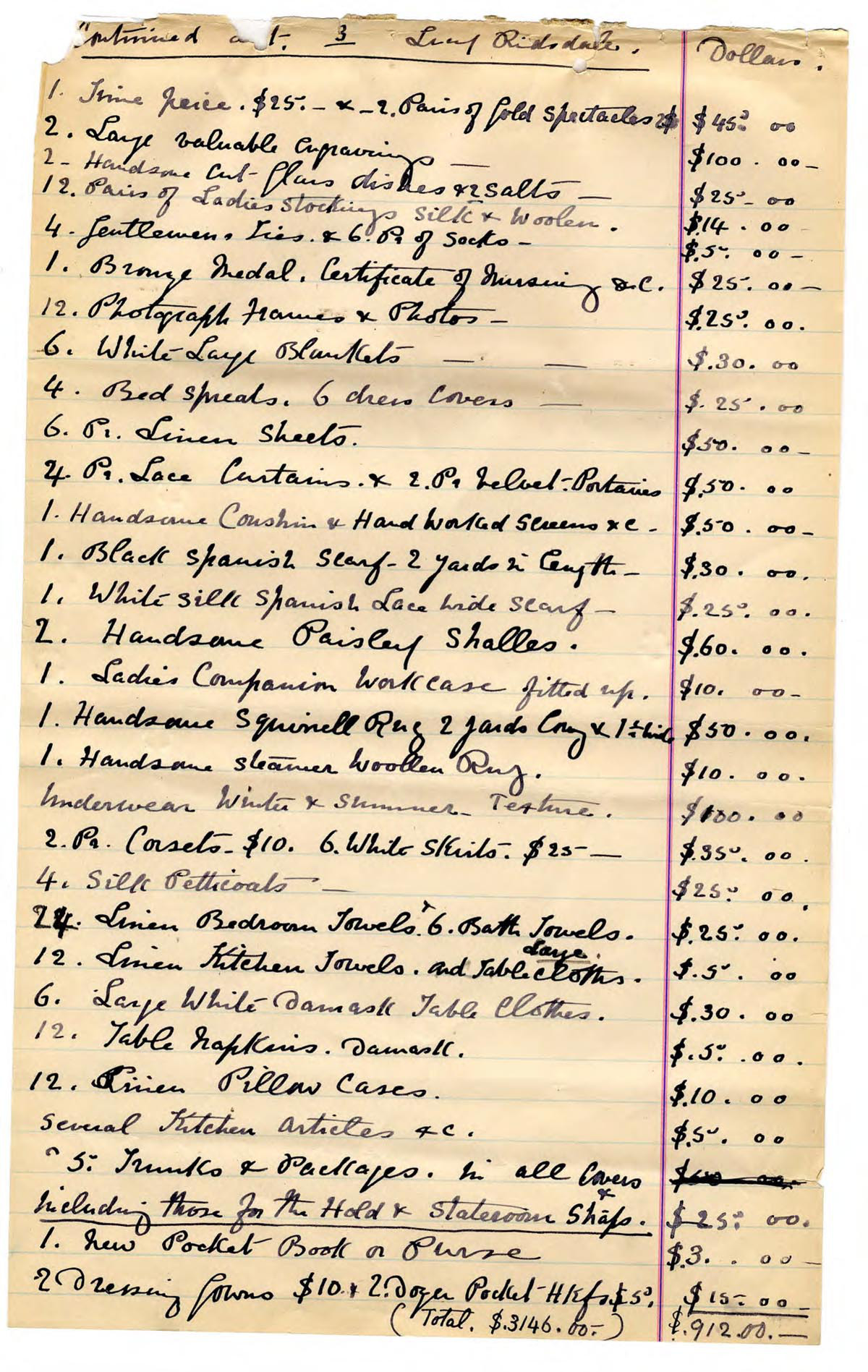

Carte-d-Inspection

Sarah's inspection ticket, required for entry into the United States.

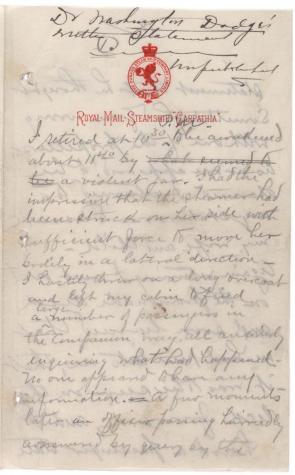

Sarah Roth letter

Letter from Sarah to her mother, written aboard Titanic

On board the ship, Sarah made friends with several passengers her age, including Emily Badman, mentioned in the above letter. When Titanic struck the iceberg, Sarah woke, sensing the ship had stopped moving. She dressed quickly and met her friends in the corridor, where they were initially told by a group of stewards that there was no need for alarm. She recalled later how a ship’s officer had prevented them from ascending a ladder to an upper deck. When they were finally allowed to use the ladder, most of the lifeboats had gone. Sarah and Emily ran toward the bow and managed to board one of the collapsible lifeboats. Sarah’s wedding dress went down with the ship.

At St. Vincent’s, the hospital staff soon learned of Sarah’s engagement to Daniel and wanted to bring some joy to the tragedy. They contacted Daniel, who professed his love for Sarah. A priest from Church of Our Lady of the Rosary agreed to officiate. Fellow survivor Emily would serve as maid-of-honor, and the Women’s Relief Committee would contribute a trousseau and bouquet.

st-vincents-ambulance

Ambulance transporting a patient to St. Vincent's Hospital

stVincentsx633

Entrance to St. Vincent's, New York's first Catholic hospital

Titanic_survivors_at_St._Vincent's_Hospital_New_York_1912

Titanic survivors at St. Vincent's

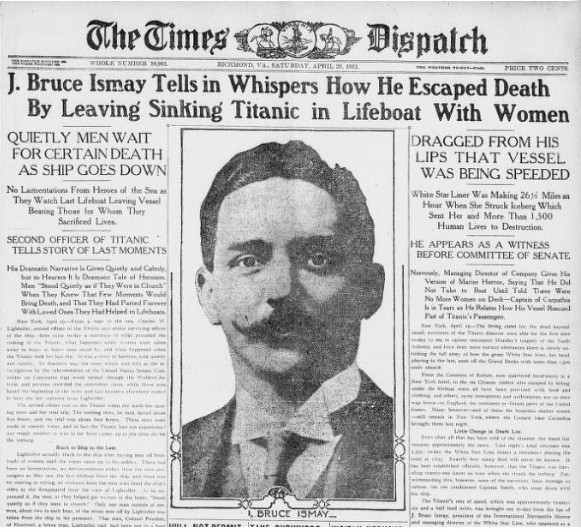

A newspaper reported, “The news of the impending wedding spread quickly through the hospital, and doctors, nurses, charity workers, patients and survivors begged to be allowed to witness the ceremony.” One of the volunteers helping at St. Vincent’s was the wealthy Mrs. Louise Vanderbilt. Following the ceremony, she was among the first of the well-wishers to congratulate the new Mr. and Mrs. Iles.

Sarah and Daniel made their home in Manhattan and had one son, named Albert Daniel. They moved to Connecticut, where Sarah died in 1947. Her husband Daniel died in 1966.

Sarah had two brothers, Harry and Samuel Roth. Harry's grandchildren, Sarah's great-nieces, have reached out to me in order to provide the following update about the living family members.

Harry had two children, Arthur and Viola. Sarah was their aunt. Arthur is now 96 years old and lives in South Carolina. He and his wife had three children, Karen, Pamela, and Charles Roth. Viola married and had four daughters--Louise, Janet, Joyce, and Carolyn. As children, they heard of Sarah's voyage and her marriage to Daniel Iles. All seven are living.

Albert, Sarah and Daniel's only child, did not have children of his own when he married, but his wife's child from a previous marriage has living descendants.

No doubt, these families will continue to share the story with generations to come of Sarah Roth and her narrow escape from the Titanic.

Photo credits: Wikimedia, Encyclopedia Titanica