Who Built the Titanic?

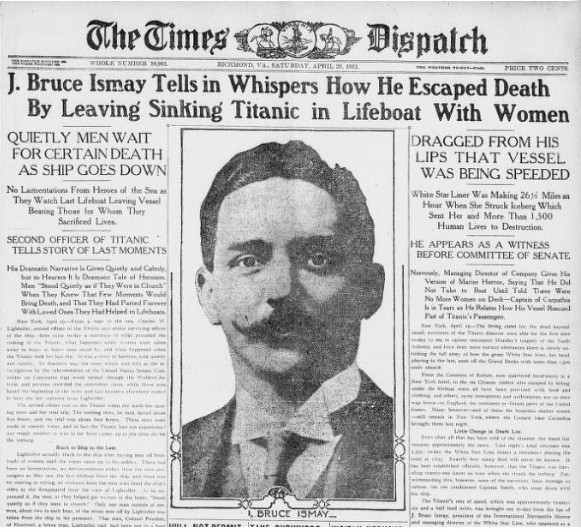

/The idea for building Titanic was born one evening in 1907 at the London home of Lord Pirrie, head of the Belfast shipbuilding company, Harland and Wolff. His dinner guest, White Star Line director J. Bruce Ismay, wanted to find a way to compete with Cunard Line’s newer, faster ships, the Mauritania and Lusitania. Knowing they couldn’t build a faster ship, Pirrie and Ismay turned to planning a series of bigger and more luxurious vessels—the most elegant ships the world had ever seen. The ships would be named the Olympic, the Titanic, and the Gigantic.

Lord Pirrie and Bruce IsmayWithin six months, construction began on Olympic and Titanic at the Harland and Wolff shipyard on the River Lagan in Belfast. Fifteen thousand workers arrived at 6:00 am every day but Sunday, and clocked out at 5:30 pm. They took a short breakfast break at 8:30 am, and a lunch break at 1:00 pm. Each man was allowed only a certain number of trips to the toilet and was timed in the process. Their pay, averaging two English pounds per week, was deducted if they were ever late for work, damaged company tools or equipment, or broke any shipyard rules. A day’s pay could be lost if a worker went to watch the launch of a ship. Everyone received one week off in summer and two days off at Christmas and at Easter.

Boys as young as 14 were often hired as apprentices. After five years of learning a specific trade, the apprentice could be qualified to join a workers’ union as a plumber, electrician, coppersmith, riveter, plater, joiner, caulker, or one of many other kinds of tradesmen.

Workers leaving Harland and Wolff at the end of a long day

Casualties were common. When Titanic was completed, 254 incidents had been recorded, with 8 fatalities. At the time, these numbers were well within the accepted rates. Two of the deaths were on the riveting squads. The squads each consisted of 4 or 5 men, and were responsible for heating, transporting, and pounding into place many thousands of rivets inside and outside the entire structure. They were paid by the rivet, so each man hurried to keep up his part of the job all day long. The fatalities occurred when two boys, aged 15 and 19, died as a result of falling while they carried red-hot rivets in their tongs to the other men on their squads.

Harland and Wolff normally chose a group of workers who were familiar with the ship to sail on its maiden voyage, called the guarantee group. No one knew the ship like they did, and who better to fix a sticking door or explain the function of some device to the crew than the ones who built it? Being selected for the guarantee group meant the worker had shown excellent skill on the job and was trusted to represent the company in a professional manner. It was a reward for a job well done, and was practically a guarantee of a good future with the company.

Titanic's Guarantee Group

Titanic’s guarantee group was led by its head designer, Thomas Andrews. At 39, Andrews was Lord Pirrie’s nephew and the man most likely to take over at Harland and Wolff one day. The eight other members of the group were:

Roderick Chisholm, chief draftsman, 43.

Anthony Frost, fitter foreman, 38.

William Parr, electrician, 29.

Robert Knight, leading hand fitter, 39.

Ennis Hastings Watson, apprentice electrician, 19.

Francis Parks, apprentice plumber, 21.

Alfred Cunningham, apprentice fitter, 21.

William Campbell, apprentice joiner, 21.

Some of the members of the guarantee group had never been far beyond Belfast, and were thrilled and honored to be taking their first transatlantic voyage on a ship they helped to build. Sadly, none of the men survived the sinking.

Photo credits: Titanicuniverse.com, Discovery Channel