A Titanic Timeline

/On this day in 1912, 2208 passengers and crew had five days until their departure from Southampton on the RMS Titanic. They came from 27 different nations and all walks of life. Many of the passengers were returning to the United States following their honeymoons, vacations, or business travels. Most had never been to America, but dreamed of a new life there. For them, these last five days would be filled with preparations, good-byes, tears, and anticipation. No one had any idea of the tragedy that would soon befall them.

1280px-Titanic_in_Southampton

April 5, Good Friday. The Titanic had passed her sea trials in Belfast and departed for Southampton, arriving in port on April 3rd. A long coal strike led several shipping companies to cancel their voyages. White Star Line sent coal from their other ships in port to Titanic, and the ship was ‘dressed’ in colorful flags and pennants as a salute to the city of Southampton.

officers

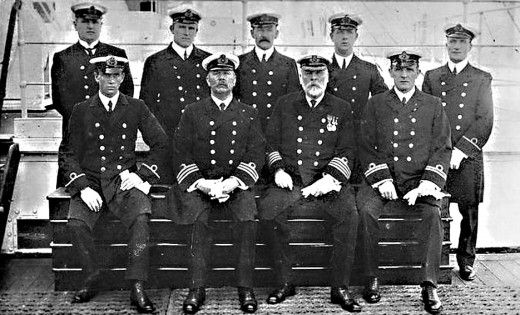

Titanic officers, with their white-bearded Captain Edward Smith

April 6. The coal strike settled and hiring began in earnest for most of Titanic’s crew. The seaman of Southampton, eager to get back to work, jammed the White Star Line hiring hall. Senior officers received assignments. Dishes, cutlery, and glassware began to arrive. Once on board, everything had to be counted and listed on the inventory before it was stored. General cargo started to arrive—crates and cartons of all manner of goods being shipped to North America.

TitanicCrane

A crane aboard Titanic used to lift cargo to the ship

April 7, Easter Sunday. All work was halted for the day, and the waterfront was deserted. Only the ship’s bell was heard, marking the hours.

April 8. Work resumed, and with only three days left until departure, many final tasks had yet to be completed. Trains brought fresh supplies to the docks, including all the food and beverages required to feed everyone on board for the week-long voyage to New York. Any last-minute problems were addressed, and every detail checked.

April 9. Thomas Andrews, Titanic’s chief architect, worked tirelessly on board, checking that all was in proper working order and noting changes he or the owner, J. Bruce Ismay, wished to make for future voyages. He wrote to his wife that evening, “The Titanic is now complete, and will I think do the old Firm credit tomorrow when we sail.”

thomas-andrews-283620-1-402

Thomas Andrews

April 10. Sailing Day. Captain Smith boarded around 7:30 a.m. Crew members came up the gangways and mustered together on various decks for orders. Passengers began to arrive around 9:30 a.m. Just before noon, Captain Smith gave the order for the whistles to be blown, announcing Titanic’s imminent departure.

Leaving Southampton

The RMS Titanic leaving Southampton

Next time, we’ll look at the following five days for Titanic. They were to be her last.

Photo credits: Encyclopediatitanica.com, Oocities.org, Spitfiresite.com

Thank you for reading! I so appreciate your following this blog, as well as your “likes” and comments. Please let me know if you have any questions or suggestions ❤