The Unstoppable Edwina Troutt

/Her father, a cabinet maker, set wood aside to build her coffin soon after she was born. But the sickly baby defied her doctors and survived. And at the age of 27, Edwina Troutt survived the sinking of the Titanic. She later said, 'I felt I was saved for something.'

young edwina

Edwina Troutt

Edwina Celia Troutt was born June 8, 1884 in Bath, England. She endured a chronic lung condition and developed pneumonia as a teenager, which left her with only one functioning lung. Still in her youth, failing eyesight and inflamed joints added to her troubles, but she refused to let anything keep her from living her life to the fullest. She became a pre-school teacher and worked in her brother-in-law's shop, then crossed the Atlantic for the first time at age 23 on a dare from friends. She planned to stay five years in New England, working in New Jersey and then in Massachusetts. But the cold New England winters were too much for her compromised respiratory system, and she returned to Bath six months early. However, her sister Elise, also living in Massachusetts by then, was about to give birth and asked Edwina (Winnie) to return, so she booked a second class cabin aboard the Titanic for the voyage back to New York.

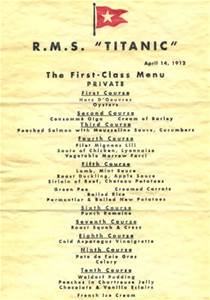

Winnie roomed with two other single women and made more friends on board, playing cards and exchanging stories with them. On Sunday, April 14th, she prepared for bed but didn't completely undress. When the ship struck the iceberg and the engines were stopped, Winnie hurried to investigate. She returned to the cabin to help her roommates to the Boat Deck. At first, Winnie stood back and watched the loading of the lifeboats and thought it sad that so many newly-married couples were being separated. Then, third class passenger Charles Thomas from Lebanon approached, holding a baby. He'd been separated from his sister-in-law, the baby's mother, and was imploring anyone within earshot to take the baby aboard a lifeboat.

Winnie immediately took the baby and boarded the next lifeboat. Later, she wrote, 'I felt I was saved for something, so I vowed never to quarrel and always be kind to the sick and elderly.' Four years later, she moved to California and met her first husband, Alfred Peterson.

edwina-troutt and peterson

Alfred and Edwina Peterson in 1923

He died in 1944, and Winnie married twice more. She became a US citizen and worked for several civic organizations. She participated in the reunions of Titanic survivors, and is remembered for her outrageous sense of humor and pleasant personality. She traveled the world to speak about the Titanic, crossing the Atlantic at least ten more times by ship.

EdwinaTroutt-Mackenzie

Edwina Troutt Peterson Corrigan Mackenzie died in California in 1984, at the age of 100.

Photo credits: denverpost.com, encyclopediatitanica.org