Titanic's Haitian Passenger

/On April 10, 1912, the Titanic departed Southampton, England and made its first stop in Cherbourg, France at 6:30 pm. Two tenders carried 281 passengers to the ship, representing 26 nationalities. Among those boarding in Cherbourg was Joseph Laroche, his wife Juliette, and their daughters, three-year-old Simonne and 21-month-old Louise. Joseph was the only black passenger to board the ship. The Laroche family were bound for Haiti, where Joseph, 25, had been born.

laroche_01

Joseph Laroche and family

During the 17th century, a French nobleman named Laroche had arrived in Haiti and married a native girl. The family had prospered, and years later, Joseph’s uncle became Haiti’s president. At age 15, Joseph left Haiti to study engineering in France, under the supervision of the Bishop of Haiti. He completed his studies, obtained an engineering position with the Paris underground, and studied English. He met his English teacher’s sister, Juliette Lafargue, and the two were married in 1908. Simonne was born the following year.

Due to racial discrimination, Joseph had difficulty finding a well-paying engineering position in France. When Juliette became pregnant with their third child in 1912, Joseph decided to move his family back to Haiti, where his uncle, the president, had arranged a job for him as a math teacher.

Joseph LaRoche

Joseph Laroche

Joseph’s mother was overjoyed to have her son and his family moving home. She paid for their first class accommodations on the liner SS France. But when Joseph and Juliette learned the ship did not allow children to dine with their parents, they cancelled their reservations and booked second class tickets on the Titanic instead.

La-gare-de-1912-501x330

Passenger boarding area in Cherbourg in 1912

On the night of Titanic's sinking, Joseph put his wife and daughters into a lifeboat. They were rescued and taken aboard the Carpathia, but Joseph perished. His body was not recovered.

Juliette and other grief-stricken young mothers on the Carpathia soon needed diapers for their children. They hid their dinner napkins by sitting on them, and put them to use as diapers.

res_1078955869_Enveloppe_Laroche

Envelope used to hold Titanic boarding passes, saved by Juliette Laroche

Juliette and her daughters were taken in temporarily by a charity in New York. She decided not to continue on to Haiti, but returned to France with the girls, where she could again be near her aging father, a widower. One month later, her son was born. She named him Joseph, after his late father.

Juliette never discussed the Titanic with anyone. Many years later in 1994, her daughter Louise met with a founding member of the Association Francaise du Titanic.“We had all been terribly affected. My mother had great difficulty talking about the disaster and she kept those atrocious images with her the rest of her life. We also received no compensation until 1918 and so ran into extreme financial difficulty.”

With the money she received six years after the disaster, Juliette opened a small fabric-dying business, which helped support her family. The girls stayed close to their mother and never married, but Juliette's son Joseph married and had three children.

In 1995, Louise helped unveil a stone marker in Cherbourg to commemorate the passengers who boarded the Titanic there 83 years earlier.

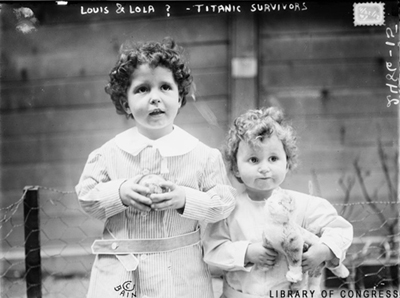

louise

Louise Laroche

In 2003, a three-act opera based on the life of Joseph Laroche premiered at the National Black Arts Festival in Atlanta, Georgia.

Photo credits: Cherbourg-titanic.com, Encyclopediatitanica.com