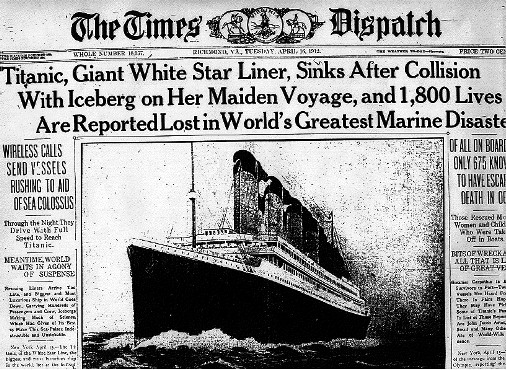

Immigrants on the Titanic

/With so many discussions of immigration at the forefront of today’s news, let’s take a look at the immigrants who boarded the Titanic. What were the immigration requirements in 1912? What happened to the immigrants who managed to survive the disaster, and how were they treated upon their arrival in New York? Between the 1880s and the 1920s, the United States experienced a great wave of immigrants pouring into the country. Between 1880 and 1900, 9 million immigrants arrived by ship in New York City. To accommodate such a large number, a new processing station was built on Ellis Island in 1892. In 1907, one million immigrants came through Ellis Island, the most in any one-year period.

Immigration processing at Ellis Island

Not every would-be immigrant was admitted to the United States. Some were sent back to their homelands if they had certain illnesses or infirmities. Others were sent to the Ellis Island hospital, or were detained while a relative recovered or until a relative or friend already living in the United States could claim them.

Each person received a brief physical examination on arrival, including a check for trachoma, a highly contagious eye infection. He or she was asked several questions regarding destination, plans for employment, and health. They were questioned whether they had ever been in a poorhouse, an asylum, or had ever had a serious illness. The main goal for federal authorities was to determine if the person could work or would otherwise become a burden to society. Men were also asked if they were polygamists. The wrong answer to any of these questions could prevent the person from entering the country.

Ellis Island arrivals examined for trachoma

Before air travel, shipping companies profited from the millions of people who wished to start new lives in America. The majority of passengers on trans-Atlantic voyages were immigrants. Many liners were overcrowded and unsanitary. The White Star Line operated several larger ships, and advertised their size and comfort. Their new Olympic class ships, Oceanic (1911), Titanic (1912), and Britannic (1914) would be the safest ships afloat and the most luxurious, even for those traveling in steerage.

On Titanic’s first and only voyage in April 1912, steerage passengers made up over half the number of passengers on the ship, and most were immigrants. White Star Line, as all the shipping companies did at the time, cooperated with the US immigration laws by screening immigrants prior to the voyage. Their names, ages, and destinations were documented on the passenger manifest.

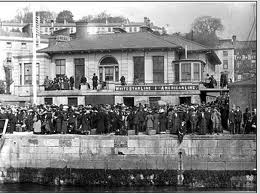

Passengers waiting to board Titanic in Queenstown, Ireland

When the Titanic sank, over three-quarters of the 709 third-class passengers were killed. The passenger manifest was also lost. Aboard the Carpathia following rescue, the crew assembled a new manifest of the survivors. In New York, federal immigration officers waived the usual examinations for the immigrant survivors. When the Carpathia arrived, the stop at Ellis Island was suspended, and the new immigrants from the Titanic were sent to hospitals or immigrant hostels. Their paperwork was processed later.

Crowd waiting to greet survivors in New York

Not all surviving immigrants from the Titanic remained in the United States. Although none were rejected by immigration officials, the disaster changed their lives. With many of their loved ones lost in the sinking, some immigrants soon chose to return to their place of birth. Others settled in America, determined to continue with their plans.

In my next post, we’ll visit 18-year-old passenger Anna Turja from Finland, who did just that.

Photo credits: EncyclopediaTitanica.org, LibertyEllisFoundation.org