Two Victims, Years Later - Titanic Honeymoons Part IV

/Clara Rogers, the daughter of well-to-do Jewish-German immigrants, found herself in an unhappy marriage and filed for divorce, despite the views of polite society in 1906. She didn’t expect to marry again, and devoted herself to raising her daughter, Nathalie. Henry Frauenthal, also raised by Jewish-German immigrants, was a brilliant orthopedic surgeon and co-founder of New York’s Hospital for Deformative and Joint Diseases. He treated patients of all races, ages and financial standings, unlike some of his medical colleagues at the time, and became famous for his new treatments for children with polio. At the height of his career, he had neither the time nor the interest in finding a wife.

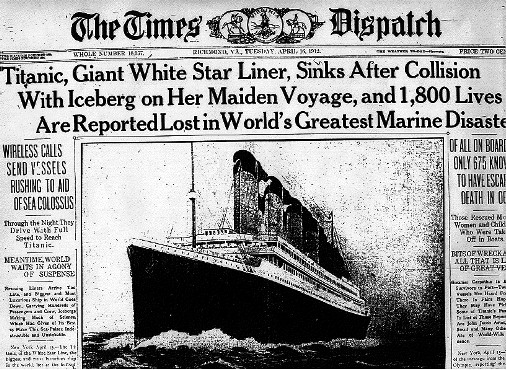

Clara and Henry met through her brother, who was active in raising funds for charitable organizations. They became friends and gradually fell in love, although neither ever expected such a thing to happen to them. With the scandal of John Jacob Astor and his young bride filling the papers, Clara and Henry decided to bypass any possible negative press and get married in Europe. Henry’s brother came along as best man, and they were married in Nice, France. Following a short honeymoon, Henry booked their first class tickets home on Titanic.

Clara and Henry Frauenthal

Henry’s skills as a physician were well-known on the ship. When a passenger tripped and fell down the Grand Staircase and broke a bone in her elbow, she refused the care of the ship’s doctor and insisted that Dr. Frauenthal attend to her. He supervised as her arm was set in a cast.

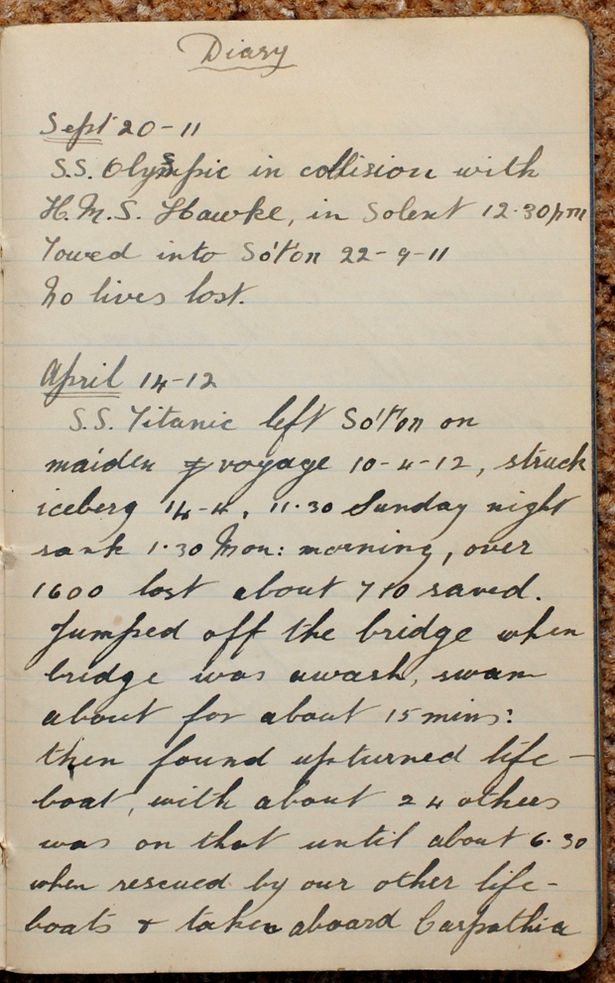

Isaac Frauenthal, Henry’s brother, told the couple about a nightmare he’d had two nights in a row onboard the ship. He recalled the vivid dream of the ship slowly sinking and the cries from terrified passengers. Then on the night of April 14, Isaac heard “a long, drawn-out rubbing noise.” He went up to A Deck and investigated until he overheard Captain Edward Smith telling John Jacob Astor they would be loading the lifeboats. Isaac hurried to wake Henry and Clara.

On the boat deck, Clara was led by Fifth Officer Harold Lowe to Lifeboat 5 and helped to board. Not wanting to leave her husband, she tried to get out but couldn’t get past those who were being lifted or helped aboard. With seats still available and Officer Lowe about to lower the boat, Henry and Isaac were allowed to board at the last minute. After the ship sank, the officer in charge of Lifeboat 5 tried to go back to pick up survivors in the water, but others in the boat feared they could all die in a rescue attempt. Henry stayed silent, knowing it would probably be too late to save anyone. He listened to the moans and cries of those in the water until they gradually subsided.

Titanic passengers disembarking Carpathia in New York City

When the Carpathia docked in New York on April 18, the Frauenthals were the first passengers to disembark. With no counseling available to the survivors or knowledge of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, everyone fended for themselves. Henry returned to work at the hospital the next day and tried to forget the horrible shock of what he and his new bride had just endured. Like other male survivors, he and his brother faced criticism for having boarded a lifeboat when so many others perished. Some of the press coverage had an anti-Semitic tone, which could have added to Henry's growing depression.

Clara and Henry avoided talking about Titanic. But Clara’s mental health was in jeopardy and Henry became increasingly depressed. In 1927, tormented by memories of the sinking and by his wife’s worsening condition, Henry jumped from the seventh floor of the hospital he founded. His funeral was attended by well over 1000 people, including many former patients. Clara was committed to a sanitarium, where she lived until her death in 1943.

New York Hospital for Joint Diseases today